Biology B

bacteria

One of two prokaryotic (no nucleus) domains, the other being the ARCHAEA. Bacteria are microscopic, simple, single-cell organisms. Some bacteria are harmless and often beneficial, playing a major role in the cycling of nutrients in ecosystems via aerobic and anaerobic decomposition (saprophytic), while others are pathogenic, causing disease and even death. Some species form symbiotic relationships with other organisms, such as legumes, and help them survive in the environment by fixing atmospheric nitrogen. Many different species exist as single cells or colonies, and they fall into four shapes based on the shape of their rigid cell wall: coccal (spherical), bacillary (rod-shaped), spirochetal (spiral/helical or corkscrew), and vibro (comma-shaped). Bacteria are also classified on the basis of oxygen requirement (aerobic vs. anaerobic).

Photomicrograph of Streptococcus (Diplococcus) pneumoniae bacteria, using Gram’sstain technique. Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the most common organisms causing respiratory infections such as pneumonia and sinusitis, as well as bacteremia, otitis media, meningitis, peritonitis, and arthritis.

In the laboratory, bacteria are classified as grampositive (blue) or gram-negative (pink) following a laboratory procedure called a Gram’s stain. Gram-negative bacteria, such as those that cause the plague, cholera, typhoid fever, and salmonella, for example, have two outer membranes, which make them more resistant to conventional treatment. They can also easily mutate and transfer these genetic changes to other strains, making them more resistant to antibiotics. Gram-positive bacteria, such as those that cause anthrax and listeriosis, are more rare and are treatable with penicillin but can cause severe damage by either releasing toxic chemicals (e.g., clostridium botulinum) or by penetrating deep into tissue (e.g., streptococci). Bacteria are often called germs.

bacteriochlorin (7,8,17,18-tetrahydroporphyrin)

bacteriochlorin (7,8,17,18-tetrahydroporphyrin) a reduced PORPHYRIN with two pairs of nonfused saturated carbon atoms (C-7, C-8 and C-17, C-18) in two of the pyrrole rings.

bacterium (plural, bacteria)

A single-celled prokaryotic microorganism in the bacteria domain.

balanced polymorphism

The maintenance of two or more alleles in a population due to the selective advantage of the heterozygote. A heterozygote is a genotype consisting of two different alleles of a gene for a particular trait (Aa). Balanced polymorphism is a type of polymorphism where the frequencies of the coexisting forms do not change noticeably over many generations. Polymorphism is a genetic trait controlled by more than one allele, each of which has a frequency of 1 percent or greater in the population gene pool. Polymorphism can also be defined as two or more phenotypes maintained in the same breeding population.

Banting, Frederick Grant

Banting, Frederick Grant (1891–1941) Canadian Physician Frederick Grant Banting was born on November 14, 1891, at Alliston, Ontario, Canada, to William Thompson Banting and Margaret Grant.

He went to secondary school at Alliston and then to the University of Toronto to study divinity before changing to the study of medicine. In 1916 he took his M.B. degree and joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps and served in France during World War I. In 1918 he was wounded at the battle of Cambrai, and the following year he was awarded the Military Cross for heroism under fire.

In 1922 he was awarded his M.D. degree and was appointed senior demonstrator in medicine at the University of Toronto. In 1923 he was elected to the Banting and Best Chair of Medical Research, which had been endowed by the legislature of the Province of Ontario.

Also in 1922, while working at the University of Toronto in the laboratory of the Scottish physiologist John James Richard MACLEOD, and with the assistance of the Canadian physiologist Charles Best, Banting discovered insulin after extracting it from the pancreas. The following year he received the Nobel Prize in medicine along with Macleod. Angered that Macleod, rather than Best, had received the Nobel Prize, Banting divided his share of the award equally with Best. It was Canada’s first Nobel Prize. He was knighted in 1934. The word banting was associated with dieting for many years.

In February 1941 he was killed in an air disaster in Newfoundland.

Bárány, Robert

Bárány, Robert (1876–1936) Austrian Physician Robert Bárány was born on April 22, 1876, in Vienna, the eldest son of the manager of a farm estate. His mother, Maria Hock, was the daughter of a well-known Prague scientist. The young Bárány contracted tuberculosis, which resulted in permanent knee problems.

He completed medical studies at Vienna University in 1900, and in 1903, he accepted a post as demonstrator at the otological clinic.

Bárány developed a rotational method for testing the middle ear, known as the vestibular system, that commands physical balance by integrating an array of neurological, biological, visual, and cognitive processes to maintain balance. The middle ear’s vestibular system is made up of three semicircular canals and an otolith. Inside the canals are fluid and hairlike cilia that register movement. As the head moves, so does the fluid, which in turn moves the cilia that send signals to the brain and nervous system. The function of the otolith, a series of calcium fibers that remain oriented to gravity, is similar. Both help the body to stay upright. Bárány’s contributions in this area won him the Nobel Prize in physiology in 1914. To receive his award, he had to be released from a Russian prisoner of war camp in 1916 at the request of the prince of Sweden.

After the war he accepted the post of principal and professor of the Otological Institute in Uppsala, where he remained for the remainder of his life.

During the latter part of his life, Bárány studied the causes of muscular rheumatism. Although he suffered a stroke, this did not prevent him from writing on the subject. He died at Uppsala on April 8, 1936. An elite organization called the Bárány Society is named after him and is devoted to vestibular research.

barchan

A crescent-shaped dune with wings, or horns, pointing downwind.

bark

The outer layer or “skin” of stems and trunks that forms a protective layer. It is composed of all the tissues outside the vascular cambium in a plant growing in thickness. Bark consists of phloem, phelloderm, cork cambium, and cork.

Barr body

One of the two X chromosomes in each somatic cell of a female is genetically inactivated. The Barr body is a dense object or mass of condensed sex chromatin lying along the inside of the nuclear envelope in female mammalian cells; it represents the inactivated X chromosome. X inactivation occurs around the 16th day of embryonic development. Mary Lyon, a British cytogeneticist, introduced the term Barr body

basal body (kinetosome)

A eukaryotic cell organelle within the cell body where a flagellum arises, which is usually composed of nine longitudinally oriented, equally spaced sets of three microtubules. They usually occur in pairs and are structurally identical to a centriole.

Not to be confused with basal body temperature (BBT), which is the lowest body temperature of the day, usually the temperature upon awakening in the morning. BBT is usually charted daily and is used to determine fertility or to achieve pregnancy.

basal metabolic rate (BMR)

BMR is the number of calories your body burns at rest to maintain normal body functions and changes with age, weight, height, gender, diet, and exercise.

base

A substance that reduces the hydrogen ion concentration in a solution. A base has less free hydrogen ions (H+) than hydroxyl ions (OH–) and has a pH of more than 7 on a scale of 0–14. A base is created when positively charged ions (base cations) such as magnesium, sodium, potassium, and calcium increase the pH of water when released to solution. They have a slippery feel in water and a bitter taste. A base will turn red litmus paper blue (acids turn blue litmus red). The three types of bases are: Arrhenius, any chemical that increases the number of free hydroxide ions (OH–) when added to a water-based solution; Bronsted or Bronsted-Lowry, any chemical that acts as a proton acceptor in a chemical reaction; and Lewis, any chemical that donates two electrons to form a covalent bond during a chemical reaction. Bases are also known as alkali or alkaline substances, and when added to acids they form salts. Some common examples of bases are soap, ammonia, and lye.

basement membrane

The thin extracellular layer composed of fibrous elements, proteins, and space-filling molecules that attaches the epithelium tissue (which forms the superficial layer of skin and some organs and the inner lining of blood vessels, ducts, body cavities, and the interior of the respiratory, digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems) to the underlying connective tissue. It is made up of a superficial basal lamina produced by the overlying epithelial tissue, and an underlying reticular lamina, which is the deeper of two layers and produced by the underlying connective tissue. It is the layer of tissue that cells “sit” or rest on.

base pairing

The specific association between two complementary strands of nucleic acids that results from the formation of hydrogen bonds between the base components (adenine [A], guanine [G], thymine [T], cytosine [C], uracil [U] of the NUCLEOTIDES of each strand (the lines indicate the number of hydrogen bonds):

A=T and G

C in DNA, A=U and G

C (and in some cases GU) in RNA

Single-stranded nucleic acid molecules can adopt a partially double-stranded structure through intrastrand base pairing.

base-pair substitution

There are two main types of mutations within a gene: base-pair substitutions and base-pair insertions or deletions. A base-pair substitution is a point mutation; it is the replacement of one nucleotide and its partner from the complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) strand with another pair of nucleotides. Bases are one of five compounds—adenine, guanine, cytosine, thymine, and uracil—that form the genetic code in DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA).

basidiomycetes

A group of fungi whose sexual spores (basidiospores) are borne in a basidium, a clubshaped reproductive cell. Includes the orders Agaricales (mushrooms) and Aphyllophorales.

basidium (plural, basidia)

) A specialized clubshaped sexual reproductive cell found in the fertile area of the hymenium, the fertile sexual spore-bearing tissues of all basidiomycetes, and that produces sexual spores on the gills of mushrooms. Shaped like a baseball bat, it possesses four slightly inwardly curved horns or spikes called sterigma on which the basidiospores are attached.

Batesian mimicry

A type of mimicry described by H. W. Bates in 1861 that describes the condition where a harmless species, the mimic, looks like a different species that is poisonous or otherwise harmful to predators, the model, and in this way gains security and protection by counterfeiting its appearance. Since many predators have become sick from eating a poisonous animal, they will avoid any similar looking animals in the future. Examples of Batesian mimicry include the Viceroy mimicking the Monarch butterfly and the clearwing moth that resembles a bee by having yellow and black coloring.

bathyal zone

The deepest part of the ocean where light does not penetrate.

B cell or lymphocyte

A type of white blood cell, or lymphocyte, that makes up 25 percent or more of the white blood cells in the body. The other class of lymphocyte is T cells. B cells develop in the bone marrow and spleen, and during infections they are transformed into plasma cells that produce large quantities of antibody (immunoglobulin) directed at specific pathogens. A cancer of the B lymphocytes is called a B-cell lymphoma.

behavioral ecology

A subdiscipline that seeks to understand the functions, or fitness consequences, of behavior in which animals interact with their environment.

Békésy, Georg von

Békésy, Georg von (1899–1972) Hungarian Physicist Georg von Békésy was born in Budapest, Hungary, on June 3, 1899, to Alexander von Békésy, a diplomat, and his wife Paula. He received his early education in Munich, Constantinople, Budapest, and in a private school in Zurich. He received a Ph.D. in physics in 1923 from the University of Budapest for a method he developed for determining molecular weight. He began working for the Hungarian Telephone and Post Office Laboratory in Budapest until 1946. During the years 1939–46 he was also professor of experimental physics at the University of Budapest.

While his research was concerned mainly with problems of long-distance telephone transmission, he conducted the study of the ear as a main component of the transmission system. He designed a telephone earphone and developed techniques for rapid, nondestructive dissection of the cochlea.

In 1946 he moved to Sweden as a guest of the Karolinska Institute and did research at the Technical Institute in Stockholm. Here he developed a new type of audiometer. The following year he moved to the United States to work at Harvard University in the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory and developed a mechanical model of the inner ear. He received the Nobel Prize in 1961 for his discoveries concerning the physical mechanisms of stimulation within the cochlea. He moved on to the University of Hawaii in 1966, where a special laboratory was built for him. He received numerous honors during his lifetime. He died on June 13, 1972, in Honolulu.

benthic zone

A lower region of a freshwater or marine body. It is below the pelagic zone and above the abyssal zone, which is the benthic zone below 9,000 m. Organisms that live on or in the sediment in these environments are called benthos.

beringia

All of the unglaciated area that encompassed northwestern North America and northeastern Asia, including the Bering Strait, during the last ice age.

berry

A pulpy and stoneless fruit containing one or more seeds, e.g., strawberry.

beta sheet

Preferentially called a beta pleated sheet; a regular structure in an extended polypeptide chain,stabilized in the form of a sheet by hydrogen bonds between CO and NH groups of adjacent (parallel or antiparallel) chains.

beta strand

Element of a BETA SHEET. One of the strands that is hydrogen bonded to a parallel or antiparallel strand to form a beta sheet.

beta turn

A hairpin structure in a polypeptide chain reversing its direction by forming a hydrogen bond between the CO group of AMINO ACID RESIDUE n with the NH group of residue (n+3).

biennia

A plant that requires two years or at least more than one season to complete its life cycle. In the first year, plants form vegetative growth, and in the second year they flower. (Latin biennialis, from biennis; bis, twice, and annus, year)

bifunctional ligand

A LIGAND that is capable of simultaneous use of two of its donor atoms to bind to one or more CENTRAL ATOMS.

bilateral symmetry

y Characterizing a body form having two similar sides—one side of an object is the mirror image of its other half—with definite upper and lower surfaces and anterior and posterior ends. Also called symmetry across an axis.

In plants, the term applies to flowers that can be divided into two equal halves by only one line through the middle. Most leaves are bilaterally symmetrical.

bilateria

Members of the branch of eumetazoans possessing bilateral symmetry. Many bilaterian animals exhibit cephalization, an evolutionary trend toward concentration of sensory structures, mouth, and nerve ganglia at the anterior end of the body. All bilaterally symmetrical animals are triploblastic, that is, having three germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm.

binary fission

A type of asexual reproduction in prokaryotes (cells or organisms lacking a membranebound, structurally discrete nucleus and other subcellular compartments) in which a cell divides or splits into two “daughter” cells, each containing a complete copy of the genetic material of the parent. Examples of organisms that reproduce this way are bacteria, paramecium, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (an ascomycetous species of yeast). Also known as transverse fission.

binding site

A specific region (or atom) in a molecular entity that is capable of entering into a stabilizing interaction with another molecular entity. An example of such an interaction is that of an ACTIVE SITE in an enzyme with its SUBSTRATE. Typical forms of interaction are by hydrogen bonding, COORDINATION, and ion-pair formation. Two binding sites in different molecular entities are said to be complementary if their interaction is stabilizing.

binomial (binomial name)

Each organism is named using a Latin-based code consisting of a combination of two names, the first being a generic (genus) name and the second a specific trivial name, which, together,constitute the scientific name of a species. Lupinus perennis, or wild blue lupine, is an example. Both names are italicized, and both names used together constitute the species name. This is an example of the binomial nomenclature, critical to the system of classification of plants and animals. Linnaeus, a Swedish naturalist, developed the system in the 18th century. The hierarchy lists the smallest group to largest group: species, genus, family, order, class, division, and kingdom. The first person to formally describe a species is often included, sometimes as an abbreviation, when the species is first mentioned in a research article (e.g., Lupinus perennis L., where L. = Linnaeus, who first produced this binomial name and provided an original description of this plant).

binuclear

Less frequently used term for the IUPAC recommended term dinuclear.

bioassay

A procedure for determining the concentration, purity, and/or biological activity of a substance (e.g., vitamin, hormone, plant growth factor, antibiotic, enzyme) by measuring its effect on an organism, tissue, cell, enzyme, or receptor preparation compared with a standard preparation.

bioavailability

The availability of a food component or a XENOBIOTIC to an organ or organism.

biocatalyst

A catalyst of biological origin, typically an ENZYME.

bioconjugate

A molecular species produced by living systems of biological origin when it is composed of two parts of different origins, e.g., a conjugate of a xenobiotic with some groups, such as glutathione, sulfate, or glucuronic acid, to make it soluble in water or compartmentalized within the cell.

bioconversion

The conversion of one substance to another by biological means. The fermentation of sugars to alcohols, catalyzed by yeasts, is an example of bioconversion.

biodiversity (biological diversity)

The totality of genes, species, and ecosystems in a particular environment, region, or the entire world. Usually refers to the variety and variability of living organisms and the ecological relationships in which they occur. It can be the number of different species and their relative frequencies in a particular area, and it can be organized on several levels, from specific species complexes to entire ecosystems or even molecular-level heredity studies.

bioenergetics

The study of the energy transfers in and between organisms and their environments and the regulation of those pathways. The term is also used for a form of psychotherapy that works through the body to engage the emotions and is based on the work of Wilhelm Reich and psychiatrist Alexander Lowen in the 1950s

biofacies

A characteristic set of fossil fauna. Facies is a geological term that means “aspect” and is used for defining subdivisions based on an aspect or characteristic of a rock formation, such as lithofacies, based on physical characteristics, or biofacies, based on the fossil content

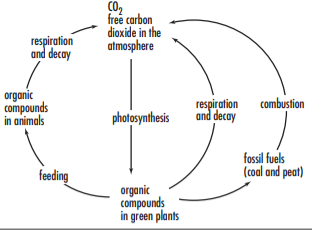

biogeochemical cycles

Both energy and inorganic nutrients flow through ecosystems. However, energy is a one-way process that drives the movement of nutrients and is then lost, whereas nutrients are cycled back into the system between organisms and their environments by way of molecules, ions, or elements. These various nutrient circuits, which involve both biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems, are called biogeochemical cycles. Major biogeochemical cycles include the water cycle, carbon cycle, oxygen cycle, nitrogen cycle, phosphorus cycle, sulfur cycle, and calcium cycle. Biogeochemical cycles can take place on a cellular level (absorption of carbon dioxide by a cell) all the way to global levels (atmosphere and ocean interactions).These cycles take place through the biosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere.

The carbon cycle, one of the main biogeochemical cycles that

processes and transfers nutrients from organisms to their environment.

biogeographic boundary

biogeographic boundary (zoogeographical region) Six to nine regions that contain broadly similar fauna. Consists of Nearctic, Palearctic, Neotropical, Aethiopian, Oriental, and Australian, and some include Holarctic, Palaeotropical, and Oceana.

biogeography

The study of the past and present distribution of life.

bioisostere (nonclassical isostere)

A compound resulting from the exchange of an atom or of a group of atoms with another broadly similar atom or group of atoms. The objective of a bioisosteric replacement is to create a new compound with similar biological properties to the parent compound. The bioisosteric replacement can be physicochemically or topologically based

bioleaching

Extraction of metals from ores or soil by biological processes, mostly by microorganisms.

biological clock

The internal timekeeping that drives or coordinates a circadian rhythm.

biological control

biological control (integrated pest management) Using living organisms to control other living organisms (pests), e.g., aphids eaten by lady beetles.

biological half-life

The time at which the amount of a biomolecule in a living organism has been reduced by one half

biological magnification

The increase in the concentration of heavy metals (e.g., mercury) or organic contaminants (e.g., chlorinated hydrocarbons [CBCs]) in organisms as a result of their consumption within a food chain/web. An excellent example is the process by which contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) accumulate or magnify as they move up the food chain. For example, PCBs concentrate in tissue and internal organs, and as big fish eat little fish, they accumulate all the PCBs that have been eaten by everyone below them in the food chain.

biological species

A population or group of populations whose members can interbreed or have the potential to interbreed.

bioluminescence

The process of producing light by a chemical reaction by a living organism, e.g., glowworms, fireflies, and jellyfish. Usually produced in organs called photopores or light organs, bioluminescence can be used for luring prey or as a courting behavior.

biomass

The dry weight of organic matter in unit area or volume, usually expressed as mass or weight of a group of organisms in a particular habitat. The term also refers to organic matter that is available on a renewable basis such as forests, agricultural crops, wood and wood wastes, animals, and plants.

biome

A large-scale recognizable grouping, a distinct ecosystem, that includes many communities of a similar nature that have adapted to a particular environment. Deserts, forests, grasslands, tundra, and the oceans are biomes. Biomes have changed naturally and moved many times during the history of life on Earth. In more recent times, change has been the result of humaninduced activity.

biomembrane

Organized sheetlike assemblies, consisting mainly of proteins and lipids (bilayers), that act as highly selective permeability barriers. Biomembranes contain specific molecular pumps and gates, receptors, and enzymes.

biomimetic

Refers to a laboratory procedure designed to imitate a natural chemical process. Also refers to a compound that mimics a biological material in its structure or function.

biomineralization

The synthesis of inorganic crystalline or amorphous mineral-like materials by living organisms. Among the minerals synthesized biologically in various forms of life are fluorapatite (Ca5(PO4)3F), hydroxyapatite, magnetite (Fe3O4), and calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

biopolymers

Macromolecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides, formed by living organisms.

bioprecursor prodrug

A PRODRUG that does not imply the linkage to a carrier group, but results from a molecular modification of the active principle itself. This modification generates a new compound, able to be transformed metabolically or chemically, the resulting compound being the active principle.

biosensor

A device that uses specific biochemical reactions mediated by isolated enzymes, immunosystems, tissues, organelles, or whole cells to detect chemical compounds, usually by electrical, thermal, or optical signals.

biosphere

e The entire portion of the Earth between the outer portion of the geosphere (the physical elements of the Earth’s surface crust and interior) and the inner portion of the atmosphere that is inhabited by life; it is the sum of all the planet’s communities and ecosystems

biotechnology

The industrial or commercial manipulation and use of living organisms or their components to improve human health and food production, either on the molecular level (genetics, gene splicing, or use of recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA]) or in more visible areas such as cattle breeding.

biotic

Pertains to the living organisms in the environment, including entire populations and ecosystems.

biotransformation

A chemical transformation mediated by living organisms or ENZYME preparations. The chemical conversion of substances by living organisms or enzyme preparations.

bivalve

e A mollusk having two valves or shells that are hinged together, e.g., mussels and clams.

blastocoel

The fluid-filled cavity that forms in the center of the blastula embryo. The blastula is an early stage in the development of an ovum, consisting of a hollow sphere of cells enclosing the blastocoel.

blastocyst

t An embryonic stage in mammals; a hollow ball of 30–150 cells produced one week after FERTILIZATION in humans. It is a sphere made up of an outer layer of cells called the trophectoderm, a fluid-filled cavity called the BLASTOCOEL, and a cluster of cells on the interior called the INNER CELL MASS. It is the inner cell mass that becomes what is known as the FETUS.

blastopore

The opening of the ARCHENTERON (primitive gut) in the gastrula that develops into the mouth in protostomes (metazoans such as the nematodes, flatworms, and mollusks that exhibit determinate, spiral cleavage and develop a mouth from the blastopore) and the anus in deuterostomes. (Animals such as the chordates and echinoderms in which the first opening in the embryo becomes the anus, while the mouth appears at the other end of the digestive system.)

blastula

Early stage of animal development of an embryo, where a ball forms consisting of a single layer of cells that surrounds the fluid-filled cavity called the blastocoel. The term blastula is often used interchangeably with the term blastocyst.

bleomycin (BLM)

A glycopeptide molecule that can serve as a metal-chelating ligand. The Fe(III) complex of bleomycin is an antitumor agent, and its activity is associated with DNA cleavage.

blood

Blood is an animal fluid that transports oxygen from the lungs to body tissues and returns carbon dioxide from body tissues to the lungs through a network of vessels such as veins, arteries, and capillaries. It transports nourishment from digestion, hormones from glands, carries disease-fighting substances to tissues, as well as wastes to the kidneys. Blood contains red and white blood cells and platelets that are responsible for a variety of functions, from transporting substances to fighting invasion from foreign substances. Some 55 percent of blood is a clear liquid called plasma. The average adult has about five liters of blood.

blood-brain barrier (BBB)

The blood-brain barrier is a collection of cells that press together to block many substances from entering the brain while allowing others to pass. It is a specialized arrangement of brain capillaries that restricts the passage of most substances into the brain, thereby preventing dramatic fluctuations in the brain’s environment. It maintains the chemical environment for neuron functions and protects the brain from the entry of foreign and harmful substances. It allows substances in the brain such as glucose, certain ions, and oxygen and others to enter, while unwanted ones are carried out by the endothelial cells. It is a defensive system to protect the central nervous system. What is little understood is how the blood-brain barrier is regulated, or why certain diseases are able to manipulate and pass through the barrier.

There is evidence that multiple sclerosis attacks occur during breakdowns of the blood-brain barrier. A study in rats showed that flavinoids, such as those found in blueberries and grape seeds among others, can inhibit blood-brain barrier breakdown under conditions that normally lead to such breakdown

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore have identified a receptor in the human brain that regulates the interface between the bloodstream and the blood-brain barrier and could lead to a new understanding of this nearly impenetrable barrier and to treatment of diseases that affect the brain. They found that two proteins, zonulin and zot, unlock the cell barrier in the intestine, attach themselves to receptors in the intestine to open the junctions between the cells, and allow substances to be absorbed. The new research indicates that zonulin and zot also react with similar receptors in the brain, suggesting that it may become feasible to develop a new generation of drugs able to cross the blood-brain barrier.

blood pressure

The hydrostatic force that blood exerts against the wall of a blood vessel. This pressure is greatest during the contraction of the ventricles of the heart (systolic pressure), which forces blood into the arterial system. Pressure falls to its lowest level when the heart is filling with blood while at rest (diastolic pressure). Blood pressure varies depending on the energy of the heart action, the elasticity of the walls of the arteries, and the volume and viscosity (resistance) of the blood. Blood pressure rises and falls throughout the day.

When the blood flows through the vessels at a greater than normal force, reading consistently above 140/90 mm Hg (millimeters of mercury), it is called hypertension or high blood pressure. High blood pressure strains the heart; harms the arteries; and increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, and kidney problems. About one in every five adults in the United States has high blood pressure. Elevated blood pressure occurs more often in men than in women, and in African Americans it occurs almost twice as often as in Caucasians. Essential hypertension (hypertension with no known cause) is not fully understood, but it accounts for about 90 percent of all hypertension cases in people over 45 years of age.

Low blood pressure is called hypotension and is an abnormal condition in which the blood pressure is lower than 90/60 mm Hg. When the blood pressure is too low, there is inadequate blood flow to the heart, brain, and other vital organs.

blotting

A technique used for transferring DNA, RNA, or protein from gels to a suitable binding matrix, such as nitrocellulose or nylon paper, while maintaining the same physical separation.

blue copper protein

An ELECTRON TRANSFER PROTEIN containing a TYPE 1 COPPER site. Characterized by a strong absorption in the visible region and an EPR (ELECTRON PARAMAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY) signal with an unusually small HYPERFINE coupling to the copper nucleus. Both characteristics are attributed to COORDINATION of the copper by a cysteine sulfur

bond energy

Atoms in a molecule are held together by covalent bonds, and to break these bonds atoms need bond energy. The source of energy to break the bonds can be in the form of heat, electricity, or mechanical means. Bond energy is the quantity of energy that must be absorbed to break a particular kind of chemical bond. It is equal to the quantity of energy the bond releases when it forms. It can also be defined as the amount of energy necessary to break one mole of bonds of a given kind (in gas phase).

bone imaging

The construction of bone tissue images from the radiation emitted by RADIONUCLIDES that have been absorbed by the bone. Radionuclides such as 18F, 85Sr, and 99mTc are introduced as complexes with specific LIGANDs (very often phosphonate ligands) and are absorbed in the bones by metabolic activity.

book lungs

s The respiratory pouches or organs of gas exchange in spiders (arachnids), consisting of closely packed blood-filled plates, sheets, or folds for maximum surface aeration and contained in an internal chamber on the underside of the abdomen. They look like the pages of a book.

Bordet, Jules

Belgian Bacteriologist, Immunologist Jules Bordet was born in Soignies, Belgium, on June 13, 1870. He was educated in Brussels and graduated with a doctor of medicine in 1892. Two years later he went to Paris and began work at the Pasteur Institute, where he worked on the destruction of bacteria and explored red blood cells in blood serum, contributing to the founding of serology, the study of immune reactions in bodily fluids. In 1901 he returned to Belgium to found the Pasteur Institute of Brabant, Brussels, where he served until 1940. He was director of the Belgian Institute and professor of bacteriology at the University of Brussels (1907–35).

His work in immunology included finding two components of blood serum responsible for bacteriolysis (rupturing of bacterial cell walls) and the process of hemolysis (rupturing of foreign red blood cells in blood serum). Working with his colleague Octave Gengou, Bordet developed several serological tests for diseases such as typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and syphilis. The bacteria responsible for whooping cough, Bordetella pertussis, was named for him after he and Gengou discovered it in 1906. In 1919, he received the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine for his immunological discoveries.

He was the author of Traité de l’immunité dans les maladies infectieuses (Treatise on immunity in infectious diseases) and numerous medical publications.

Bordet was a permanent member of the administrative council of Brussels University, president of the First International Congress of Microbiology (Paris, 1930), and member of numerous scientific societies. He died on April 6, 1961.

bottleneck effect

A dramatic reduction in genetic diversity of a population or species when the population number is severely depleted by natural disaster, by disease, or by changed environmental conditions. This limits genetic diversity, since the few survivors are the resulting genetic pool from which all future generations are based.

Bovet, Daniels (1907–1992)

Swiss Physiologist Daniel Bovet was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on March 23, 1907, to Pierre Bovet, professor of pedagogy at the University of Geneva, and Amy Babut. He graduated from the University of Geneva in 1927 and then worked on a doctorate in zoology and comparative anatomy, which he received in 1929.

During the years 1929 until 1947 he worked at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, starting as an assistant and later as chief of the institute’s Laboratory of Therapeutic Chemistry. Here he discovered the first synthetic antihistamine, pyrilamine (meplyramine). In 1947 he went to Rome to organize a laboratory of therapeutic chemistry and became an Italian citizen. He became the laboratory’s chief at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome. Seeking a substitute for curare, a muscle relaxant, for anesthesia, he discovered gallamine (tradename Flaxedil), a neuromuscular blocking agent used today as a muscle relaxant in the administration of anesthesia.

esthesia. He and his wife Filomena Nitti published two important books, Structure chimique et activité pharmacodynamique des médicaments du système nerveux végétatif (The chemical structure and pharmacodynamic activity of drugs of the vegetative nervous system) in 1948 and, with G. B. Marini-Bettòlo, Curare and Curare-like Agents (1959). In 1957 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine for his discovery relating to synthetic compounds for the blocking of the effects of certain substances occurring in the body, especially in its blood vessels and skeletal muscles

Bovet published more than 300 papers and received numerous awards. He served as the head of the psychobiology and psychopharmacology laboratory of the National Research Council (Rome) from 1969 until 1971, when he became professor of psychobiology at the University of Rome (1971–82). He died on April 8, 1992, in Rome.

Bowman’s capsule

A cup-shaped receptacle in the kidney that contains the glomerulus, a semipermeable twisted mass of tiny tubes through which the blood passes and is the primary filtering device of the nephron, a tiny structure that produces urine during the process of removing wastes. Each kidney is made up of about 1 million nephrons. Blood is transported into the Bowman’s capsule from the afferent arteriole that branches off of the interlobular artery. The blood is filtered out within the capsule, through the glomerulus, and then passes out by way of the efferent arteriole. The filtered water and aqueous wastes are passed out of the Bowman’s capsule into the proximal convoluted tubule, where it passes through the loop of Heinle and into the distal convoluted tubule. Eventually the urine passes and filters through the tiny ducts of the calyces, the smallest part of the kidney collecting system, where it begins to be collected and passes down into the pelvis of the kidney before it makes its way to the ureter and to the bladder for elimination.

brachyptery

A condition where wings are disproportionately small in relation to the body.

brain imaging

In addition to MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING, which is based on the absorption by the brain of electromagnetic radiation, brain images can be acquired by scintillation counting (scintigraphy) of radiation emitted from radioactive nuclei that have crossed the blood-brain barrier. The introduction of radionuclides into brain tissue is accomplished with the use of specific 99mTc(V) complexes with lipophilic ligands

brain stem (brainstem)

The oldest and inferior portion of the brain that consists of the midbrain, pons, reticular formation, thalamus, and medulla oblongata,and forms a cap on the anterior end of the spinal cord. The brain stem is the base of the brain and connects the brain’s cerebrum to the spinal cord. It shares several features in common with the brain of reptiles and controls automatic and motor basic functions such as heart rate and respiration and also is the main channel for sensory and motor signals.

bridging ligand

A bridging ligand binds to two or more CENTRAL ATOMs, usually metals, thereby linking them together to produce polynuclear coordination entities. Bridging is indicated by the Greek letter µ appearing before the ligand name and separated by a hyphen. For an example, see FEMO-COFACTOR.

bronchiole

A series of small tubes or airway passages that branch from the larger tertiary bronchi within each lung. At the end of the bronchiole are the alveoli, thousands of small saclike structures that make up the bulk of the lung and where used blood gets reoxygenated before routing back through the heart.

Brønsted acid

A molecular entity capable of donating a hydron to a base (i.e., a “hydron donor”) or the corresponding chemical species.

Brønsted base

A molecular entity capable of accepting a hydron from an acid (i.e., a “hydron acceptor”) or the corresponding chemical species

Brownian movement

The rapid but random motion of particles colliding with molecules of a gas or liquid in which they are suspended.

bryophytes

The mosses (Bryophyta), liverworts (Hepatophyta), and hornworts (Anthocerophyta); a group of small, rootless, thalloid (single cell, colony, filament of cells, or a large branching multicellular structure) or leafy nonvascular plants with life cycles dominated by the gametophyte phase. These plants inhabit the land but lack many of the terrestrial adaptations of vascular plants, such as specialized vascular or transporting tissues (e.g., xylem and phloem).

Terrestrial bryophytes are important for soil fixation and humus buildup. In pioneer vegetation, they provide a suitable habitat for seedlings of early pioneering plants. Bryophytes are also early colonizers after fire and contribute to nutrient cycles.

bubonic plague

A bacterial disease marked by chills, fever, and inflammatory swelling of lymphatic glands found in rodents and humans. It is caused by Pasteurella pestis and transmitted by the oriental rat flea. The famous Black Death that devastated the population of Europe and Asia in the 1300s was a form of bubonic plague.

budding

An asexual means of propagation in which a group of self-supportive outgrowths (buds) from the parent form and detach to live independently, or else remain attached to eventually form extensive colonies. The propagation of yeast is a good example of budding

Also a type of grafting that consists of inserting a single bud into a stock.

buffer

A molecule or chemical used to control the pH of a solution. It consists of acid and base forms and minimizes changes in pH when extraneous acids or bases are added to the solution. It prevents large changes in pH by either combining with H+ or by releasing H+ into solution.

bulk flow (pressure flow)

Movement of water due to a difference in pressure between two locations. The movement of solutes in plant phloem tissue is an example.

New Jersey casinos: 2021 in play | JT Hub

ReplyDeleteNew Jersey casino site: PlayNJ offers a slew of legal 고양 출장샵 casino options for players The New Jersey 여수 출장마사지 gambling authority 군산 출장안마 recently launched its 충주 출장안마 sportsbook, Sportsbook, and 사천 출장샵